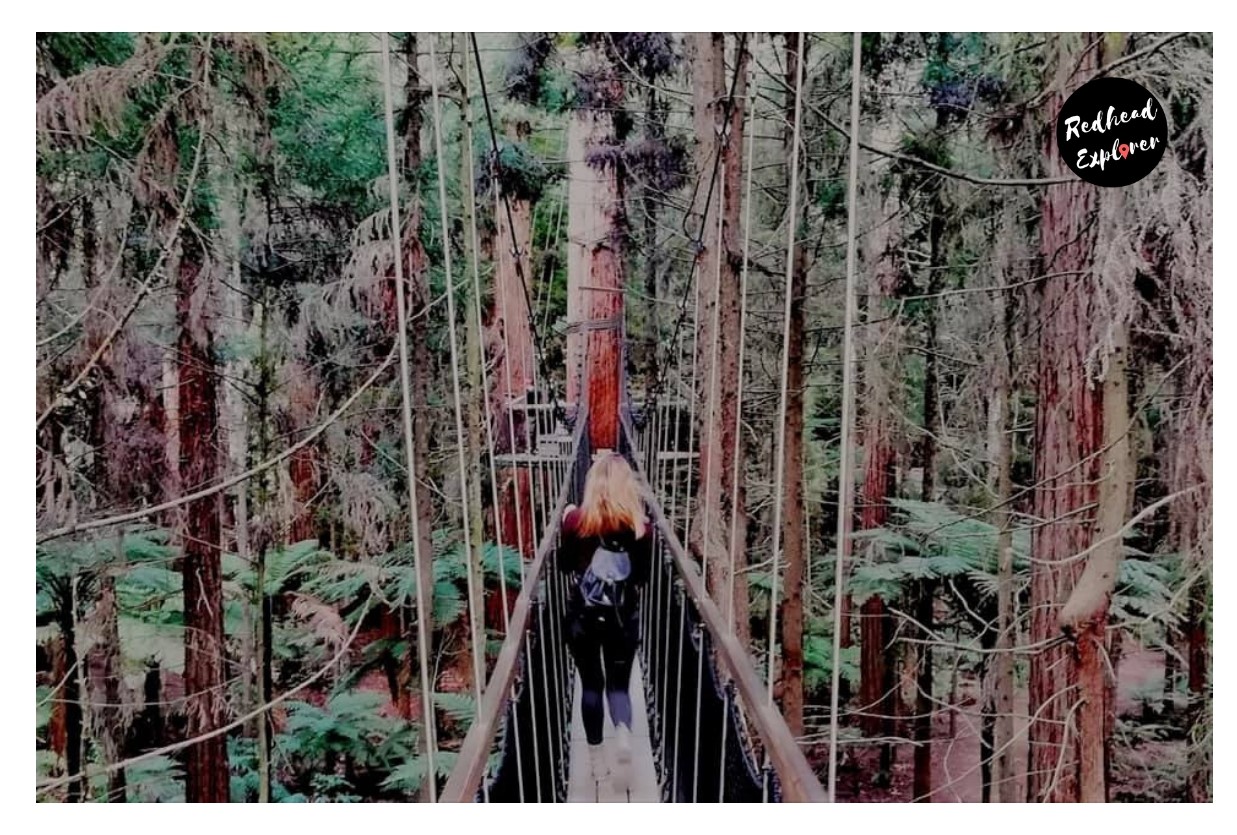

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the effects of permanent travel, of the long-term journeys we make when we decide to work, study or live abroad. It is easy to focus on the picture-perfect moments of it, but the truth is that it is not an easy journey.

Nomads, vagabonds. Call us what you will (I want to meet you if you get the reference), but our home is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Because of this even the happiest journeys can sometimes overwhelm you and remind you how much you (do not) miss about home.

Are we there yet?

When you move to live in a new country, you leave your comfort zone and stretch your limits. And let’s be honest: it is as terrifying, as it is exciting. It is an opportunity, but it also a huge blank to be filled.

You are yet to settle;

yet to find new friends;

yet to fit;

yet to rebuild a semblance of your old, comfortably familiar life.

When we finally got all our documents sorted out and the path was clear for me and Stef to move to New Zealand, I was ecstatic. The problem with being ecstatic is that you can really underestimate the time it really takes to make a proper transition from one culture to another.

Even if you have travelled or lived abroad multiple times, you are not immune to experiencing a culture shock when you least expect it. Adaptation is a process: no matter how many times you have gone through it: it takes time, patience and a hefty dose of determination and self-awareness.

Factors which impact transition

Before New Zealand, I had lived for a year on the other side of the Pacific (in hip Seattle before the Amazon craze) and I also spend almost a year in a small town on the Eastern coast of Italy. Ironically, neither experience really helped me to prepare emotionally for my first year here in New Zealand.

- Each country is its own microcosm. No matter how many times you have travelled or lived somewhere else, each culture has its own peculiar features. Adapting quickly to one place is no guarantee a seamless transition in another one

- What stage in your life are you? When I was 20, I was ready to leave in a heartbeat. But as your friendships grow stronger and your values shift, you start to realise that many things of fundamental importance take years to build. The very thought of this makes moving somewhere much harder

- How long will you be staying abroad? Moving for a short job contract or a study exchange is radically different from packing your old life into several suitcases and leaving for (at least) several years

- Are you sure you speak the same language? I am not talking about language barriers, I mean the many tiny cultural rules, spreading like an invisible web around you. Communication is about more than words: it involves values, attitudes, cultural norms. Navigating through them can range from hilarious and exciting to downright frustrating and alienating

- Your relationships will have a significant impact on the experience. The closer you are to your family and your friends, the harder it would be to leave them behind. I have the luxury of sharing the adventure with my favourite person in the world which surely makes things much easier than starting somewhere else on your own. However, even if you move with your partner (and kids), prepare for spells of incredibly tough nostalgia and homesickness for friends and family.

What is home? Where is it? And who are you away from it?

I asked one of my best friends when was the first time he felt at home after moving abroad. He told me he never really did. And that home is no longer home either.

Research and interviews with many people consistently echo this notion of being stranded. Uprooted. Unsettled. There is culture shock abroad and there is reverse culture shock when you come back home: you keep adapting, re-adapting and fighting change, whether you realise it or not.

Things which are self-evident to locals (cultural norms, social behaviour) can be downright bewildering to you. Things which are outrageous to them are just everyday life for you. I literally had to relearn how to walk properly: we usually walk on the right-hand side and in New Zealand (probably because they also drive on the left) pedestrians walk on the left side curb. I kept bumping into people for a few days before I realised almost everything I considered “normal” was the opposite way around.

When you live in a different country there is a constant (re)negotiation of behaviour, cultural context, social norms and even personal values. Sometimes this happens through a lot of internal conflict and frustration, other times it is gradual and subtle: you don’t even realise you are shifting your behaviour and beliefs.

Adapting and (re)learning can be a good thing. After all, what is the point of moving to a new country if you are going to do absolutely everything the same way you always did? I understand why immigrants and expats often seek a community from their country of origin. The warm feeling of familiarity is comforting and worth pursuing. However, when you only seek people who speak the same language and have the exact same values and norms, you lock yourself in a bubble. You are physically in another country but mentally you are not there at all. This is harmful in the long term because instead of bridges, you are just building islands and functioning societies cannot be built across disconnected islands. On the other hand, your background is an essential part of who you are: you must own it and cherish it. Forsaking your native language and completely disconnecting yourself from your culture creates alienation and sooner or later leads to resentment: both on your side and from your own culture.

There is always a middle way. I choose to appreciate and cherish my origin, yet I refuse to close my eyes when I see dysfunctional things in my native culture.

Dealing with Prejudice

Moving to another country often requires you to rebuild and reclaim your identity. This can be challenging when you no longer have the support structures (family, friends, communities you have built over time) which shaped it. On top of that, as an outsider, you often have to navigate through biases and prejudice.

Kiwis are incredibly kind and welcoming, so getting along with people here is a breeze. However, I know from my past experience that for many people it is easier, faster and more convenient to think in boxes, to rely on simplifications and stereotypes. Otherwise, you would have to do the hard work to truly get to know others.

During my other travels, I have met a fair share of people who would not even try to hide their prejudice about my country. People who have a default believe that Eastern Europe is some kind of a poor wasteland, tucked away at the cultural periphery of Europe.

I love it when such people ask me “Do you have Coca Cola/fridges/raisins/recruitment agencies in Bulgaria?”, without even realising they are talking about one of the oldest countries in Europe (founded in 681 AD). In fact, the Cyrillic alphabet of all Slavic nations originated in Bulgaria during a period of cultural upheaval comparable to the Carolingian Renaissance. So no, we do not live in caves. We just had a devastating historical dance with socialism which lasted for several destructive decades.

So why do we conflate wealth with worth? And why do we assume that people in less affluent countries are qualitatively different? Why would each individual have the same characteristics as the other few (hundred) million people sharing the same geographic area? It is a ridiculous notion. All over the world, there are people who are bright, entrepreneurial, talented and highly skilled at something: regardless of where they were born.

If anything, you can be sure that your immigrant colleagues and peers who come from countries with worse economies and social structures, had to fight 10x times harder than you did, to be able to get to the same place. Respect that.

You probably have preconceived notions and stereotypes about other people and other countries and when you go somewhere the locals might have prejudice and stereotypes about your culture, as well. An easy way to understand the harmfulness of prejudice is to…take a look at yourself. Think of the worst stereotype about your nation or about the worst group of people in your nation whose behaviour makes your blood boil. Would you like strangers to assume that this is who YOU are?

People should be judged by their personal character, actions and accomplishments, not by the merits of the group they seem to belong to. As an immigrant/expat/newcomer to a new culture, your identity will be under constant attack so it is really important to preserve your self-respect even when you have to face biases and prejudice. Even if some people around you see you as an outsider, you don’t have to feel like one. Real confidence comes from respecting your worth while having humility about your limitations. To quote Tyrion: Never forget what you are. The rest of the world will not. Wear it like armor, and it can never be used to hurt you.

Adapting to a new culture

There is a multitude of psychological processes underlying the adaptation to a new culture. The work of Australian psychologist Stephen Bochner (1986, 2003) sheds light on how people adapt to new cultural contexts. In everyday life we often talk about adjustment: Bochner defines it as an active, adaptive response in which the person moving to a new culture has to accommodate to it “or suffer the consequences”. This view emphasises the superiority of the host culture and the notion that it is should eventually override the culture of the traveller/expat.

Instead of such a static, monolithic approach, Bochner focuses on culture-learning and the behavioural aspects of exchange between cultures. In this approach moving to a new culture is seen not as trying to fit into a cultural mold, but as an act of developing new skills: language skills, social skills, a better understanding of cultural norms and behaviours, and so on.

Some critical factors for successful adjustment in a new country are, thus, linked to activities emphasising interactions, relationships and instrumental skills (Do you have local friends or stick only to members of your own ethnic/cultural group? Do you form meaningful links or just trivial, superficial relationships with members of the host society?)

There is also a personal component: if you are not interested in other cultures or have a low tolerance for them, adjustment to a new host society would be much more difficult. Your attitude and individual predispositions are of key importance: if you are averse to experiencing new and unusual cultural environments, your attitude is more likely to be negative and this prevents you from having a meaningful transition from your home society to the new one.

Environmental factors are also important. Personal efforts need to be met half-way by some level of host receptivity (openness to accept newcomers and interact with them). Some cultures are more open to outsiders, others are more homogenous and selective. The same society may also have different reactions to outsiders depending on how closely related or distant they are to the local culture.

Building Friendships

We feel lucky that New Zealanders are such a lovely, friendly nation full of people who are ready to help and reach out. However, it takes time to turn social interactions into deep, long-lasting relationships. Even if you hit it off instantly with another person, it takes years or even decades for a relationship to become as close as the ones you have back home.

On that note, I don’t really agree when people who live abroad describe the locals as “cold”, “hypocritical” or “just pretending to be friends”. I think they just take their time and have more (healthy) personal boundaries. Eastern Europeans and people from Southern nations need 20 minutes to start hugging another person and sharing their life’s story. In Western cultures, it just takes more time to establish whether an acquaintance is deemed to become a friend. And that’s alright by me: I appreciate the notion of earning respect and building a relationship rather than jumping right into someone’s personal space.

Furthermore, I think there is one simple reason why locals act the way they do. They have a life, and (in this new situation) you don’t. You are in a new country, you are away from friends and family and you have a vested interest in building relationships as quickly as possible. But for the locals, this simply isn’t so. Even if they really like you, they probably have a ton of things to do, places to be and relationships to handle.

Friendships take time to develop and if you are in your late 20s or older, you are at a disadvantage. By this age most people have already have formed strong friendships, many have serious relationships (and often kids), busy work schedules and tons of errands to run...Even those who think you are awesome, probably need to work extra hard to find time to hang out with you. I think it is a safe bet to say that in Western societies the little free time people have is most likely scheduled for days or weeks in advance.

That is why, it is easier to make friends with other travellers/newcomers/expats. They are also new to the local culture (and thus share experiences, needs and frustrations with you). Sometimes they come from the same cultural or linguistic background so communication is easier. And most of all: they also crave friendships similar to those they had in their home country, so they are willing to invest more time and effort to build a social network.

So don’t take it personally, if friendships do not move as fast (or as easy) as you wish. Take your time and don’t give up. It can get really hard (and lonely) in the first months or even a year, but if you don’t lose sight of your goals and values, you will find the right place and the right people.

Leave a comment